St. Mary’s School for Indian Girls

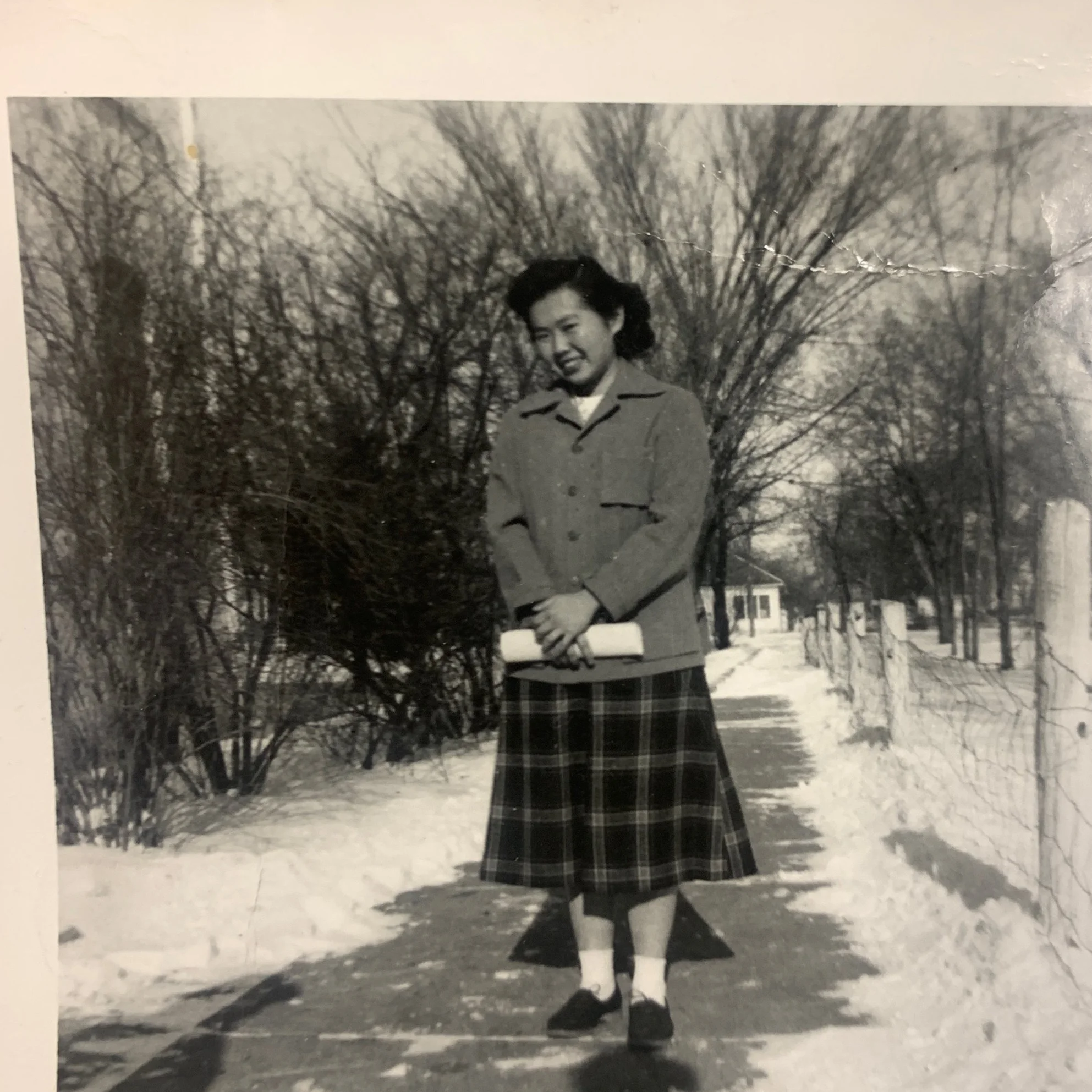

Not sure how long it has been since you were in my parents' living room, but you may remember that there is a shadow box that hangs over the dining room table. In the shadow box is a pair of beaded moccasins for an adult, and a pair for a baby, and a brightly beaded belt. When I was little, I asked about the moccasins, and was told that they were a gift that Nana (June) received from Native Americans in South Dakota. When I got a little bit older, I asked for more info, and was told as much as my Mom could remember: When Nana graduated from college in Rhode Island, her parents were still in Internment, and so going back to California wasn't an option. She felt a great debt to the Episcopal Church (since it was their "sponsorship" of her that had gotten her out of Internment, and able to attend college in the first place). She reached out to the Church to ask if she could be of service, and they told her they could use her as a teacher at St. Mary's School—a school for Native American girls in South Dakota. On her own, Nana graduated college and headed to South Dakota in the middle of the winter of '46. She was at St. Mary's only about a year, because when her parents were released from Internment, they wrote to her to tell her that it was time to come home and get married, before she became an "Old Maid." She obeyed. Someone gave her the moccasins and belt as a goodbye gift.

For most of my life, that was all the info I had. When Ma and I made the little documentary about Nana (when I was in fourth grade), we didn't find any photos of her at St. Mary's or on the Reservation. No documents. No artifacts other than the moccasins. I sort of always assumed it was a lost story. But I loved the small bits of fable that I could string together: Nana learning to eat deer, Nana learning to drive stick shift. It seemed like she had had an incredible adventure. And as I got older, there was something important to me about the juxtaposition of being on a Native American reservation while her parents were interned. I couldn't quite put my thumb on why, but it stuck with me. I ended up writing this poem about it.

This past January, I performed that poem in a show in LA, and a little while afterward, my friend Charlie reached out. I had met Charlie last summer, but we had only hung out twice. She had mentioned that she grew up in South Dakota, but had lived in LA since graduating from college. After my January show, Charlie texted me to ask if I knew the name of the school where my grandmother had taught. I told her the name, and she googled around to find that there had been a "St. Mary's School" on Rosebud Reservation. Charlie's father is a radiologist whose work is on Rosebud Reservation, so he is there many days a week. Charlie told me that she was sure that if we could find somebody who was still alive and didn't suffer from Dementia, that they would likely remember Nana. (Very few people leave the Reservation, she told me, and a Japanese American woman would have stood out at the time!)

Charlie started doing some digging and was connected to a woman named Virginia, via email. Charlie emailed Virginia to ask whether she remembered a June Suzuki at St. Mary's School, and received this email in response:

Dear Charlie,

I remember June Suzuki at St. Mary's when I was a student there. I don't think I took a class from her, but do remember her from study hall and eating at her table in the dining room. I do recall that she told us about how her family was removed from their home, taking only what they could carry and sent to an Internment camp. We girls we appaled [sic] at how our government treated the Japanese and imprisoning them. I'll never forget her response, "what do you think reservations are?" She opened my eyes to the tragic history of my own family and people.

June Suzuki

““She told us about how her family was removed from their home, taking only what they could carry and sent to an Interment camp. We girls we appaled at how our government treated the Japanese and imprisoning them. I’ll never forget her response, ‘what do you think reservations are?’ She opened my eyes to the tragic history of my own family and people.”— Virginia Driving Hawk Sneve”

I was totally stunned by this letter. First, because I couldn't believe we had found somebody who knew/remembered Nana, and second, because I couldn't imagine the June Suzuki I knew ever saying something so political. But this was a younger June Suzuki—one I never knew. Charlie and I immediately started to plan a trip to South Dakota to try and meet Virginia in person, but also to see if we could find anyone else with information about Nana, or about St. Mary's, or about what life might have been like on the Reservation during or immediately after World War II.

On June 1st, I flew down to South Dakota, and after a day of hanging out with some buffalo and getting lost in the Badlands, we drove to find Virginia. Here is what she looks like. She sat with us for almost 2 hours, chatting about what she remembered. She was only ten or eleven when Nana was at St. Mary's (which is why she wasn't one of her students—Nana taught the older girls), and she didn't spend that much time with her. But she retold the story she had written in her email, and hearing her share it was incredibly special to me. (You can listen to her say it herself, here!) She also gave us a very important piece of information (or "clue," as I like to think of it!). I had always thought Nana was on a Reservation when she was at St. Mary's. And when Charlie had googled St. Mary's, she had found info that suggested it was on Rosebud Reservation. Our plan was to drive around Rosebud after we left Virginia, and see if we could find it. But Virginia told us that when Nana was at St. Mary's, it wasn't on a reservation at all. St. Mary's was originally built at the Santee Mission in Nebraska, but when it burned down in 1884, it was rebuilt in Rosebud. It burned down again in 1910, and again in 1922. The third time, it was moved to a spot across the river from its original home in Santee, to a historical building in Springfield, South Dakota, overlooking the Missouri River. This is where the school was when Nana arrived to it in 1946. So she hadn't been on a reservation. Instead, girls from many different tribes and reservations across multiple states were brought to St. Mary's and instructed by the small staff of non-native teachers, of which Nana was the only non-white person (during her year there). Virginia told us there were Lakota girls from Rosebud or Pine Ridge in South Dakota (which is what Virginia is), but also some Navajos from the west, and Chippewas from Minnesota. It's very possible that Nana did end up spending time on a Reservation at some point, though. For one thing, when I described learning to shoot or prepare deer, Virginia seemed sure that that was something they would not have done at school. The moccasins too, she thought, seemed like the kind of gift that would come from a family, perhaps one that Nana had visited or stayed with during a school vacation. Virginia shared what she remembered of St. Mary's, and these were the details I latched onto most:

the sleeping quarters, classrooms, chapel, gym, showers, and dining hall were all in the same building, on different floors, so for the most part, they spent their days in the same building, with small trips to town on weekends, or hikes along the river.

there was only a small staff of 6-7 teachers, only about 40-70 girls in the whole school at once, depending on the year. All the teachers were non-Native, and the only staff members who were Native were Virginia's grandparents, who worked as custodians at the school.

the girls were required to wear scratchy woolen tights that itched terribly.

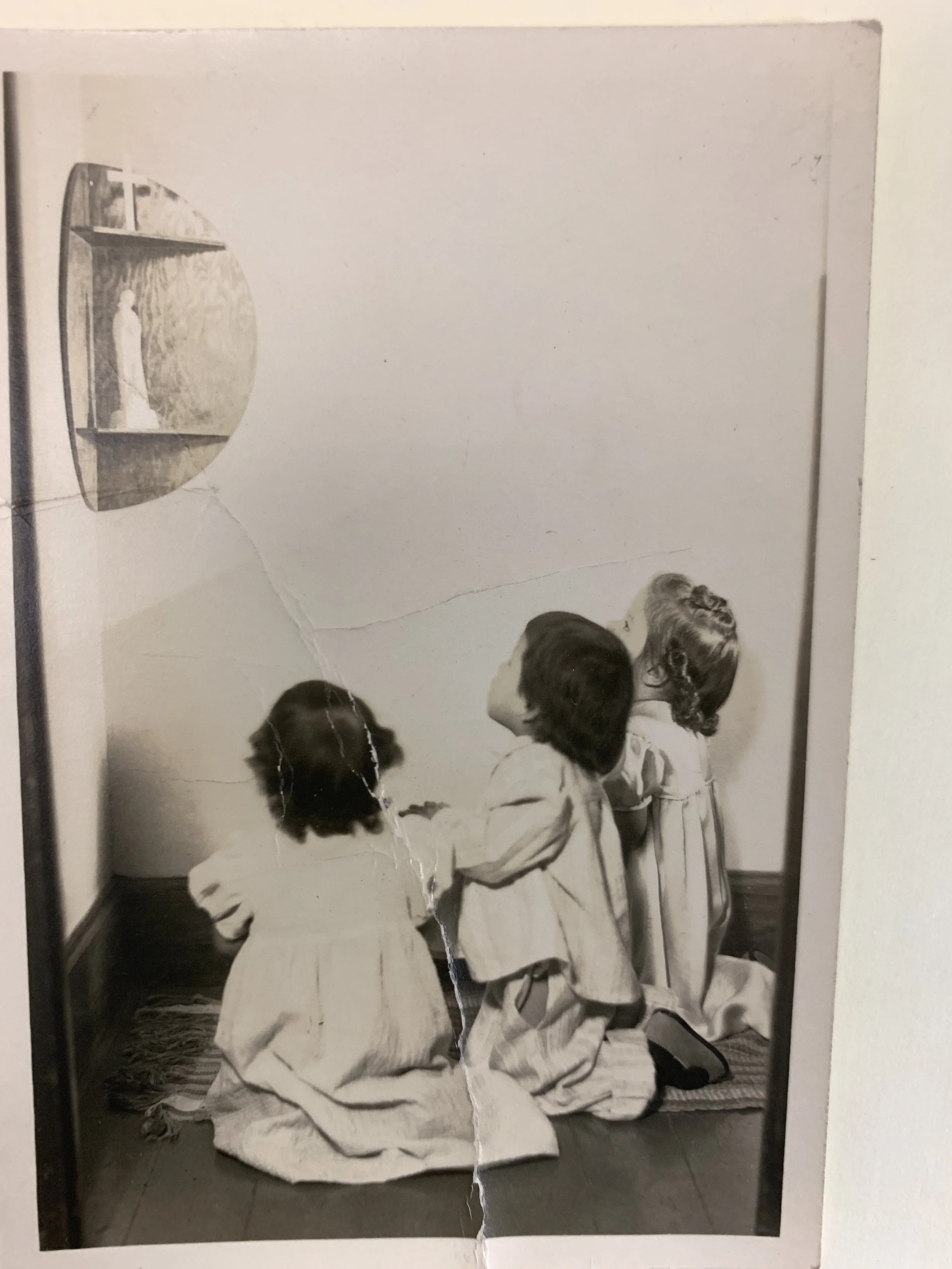

everyone took piano / organ lessons, and many of the girls went on to be organists in their local episcopal churches. (Virginia was one for a while).

everyone had chores to do, like helping with the cooking or cleaning.

they almost never interacted with boys, except once or twice a year when there were school dances held with the boys from Hare School, the Episcopal boys school (far away), and Virginia described herself as being very shy, though she felt the dances were fun.

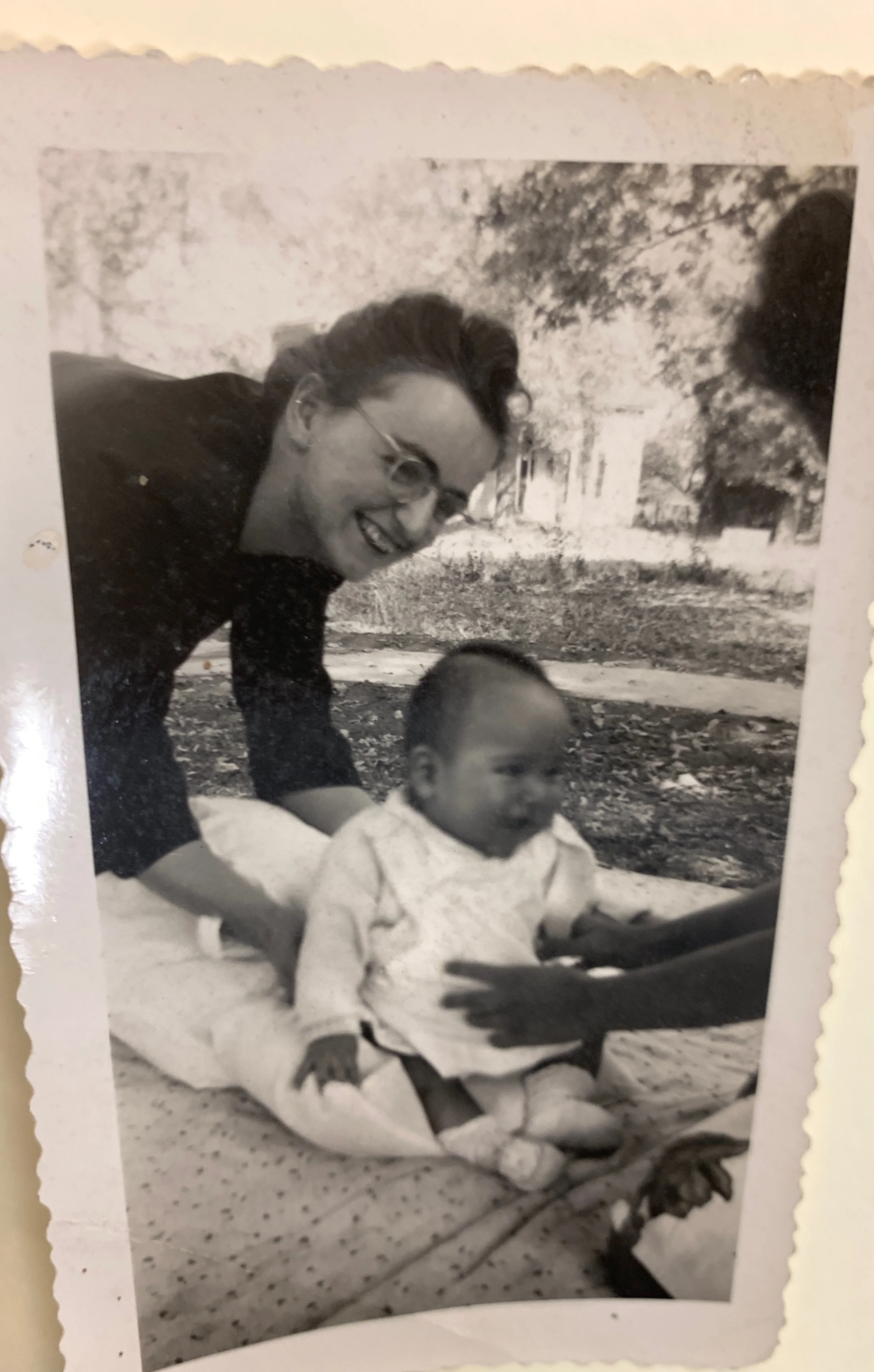

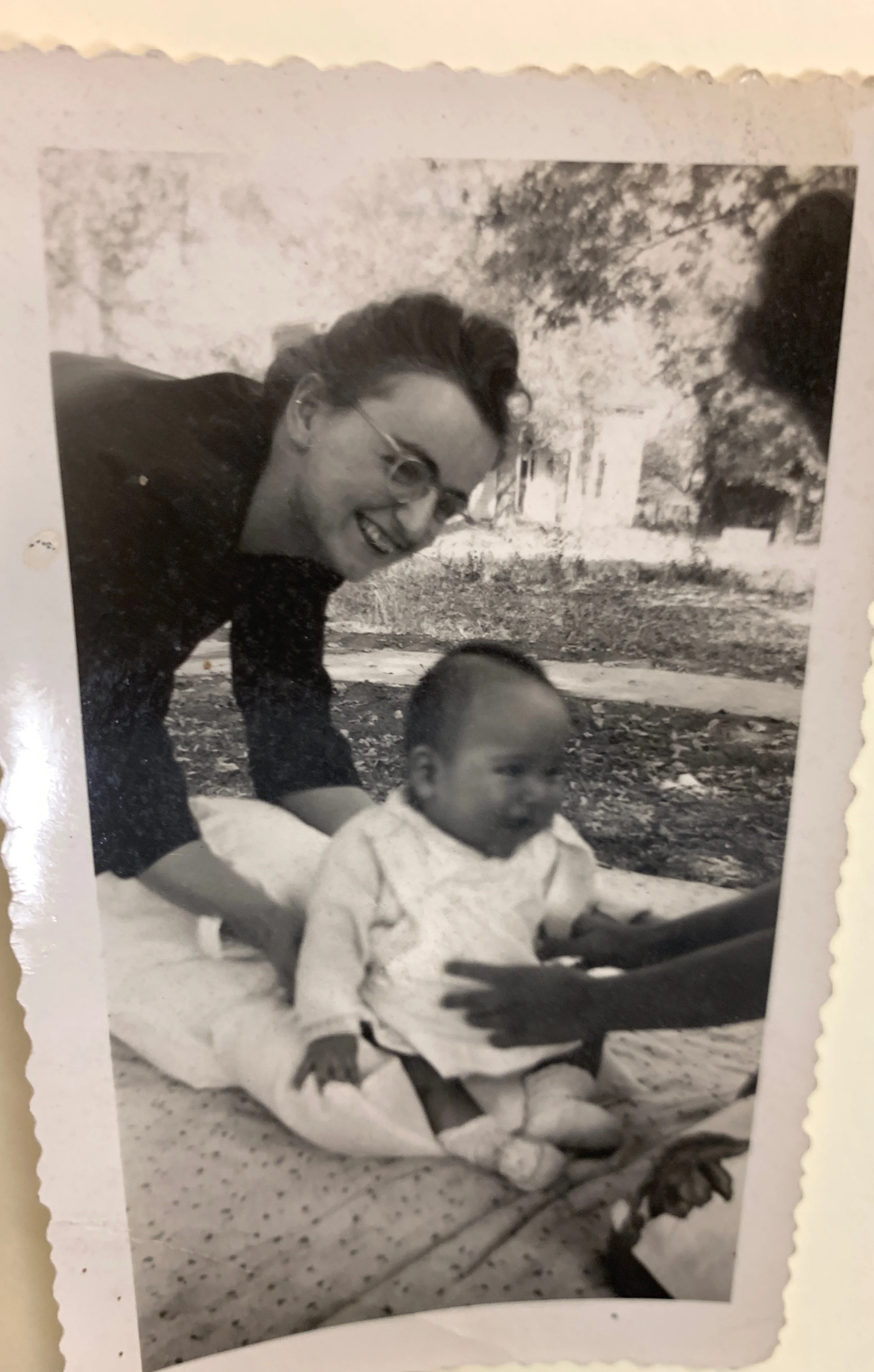

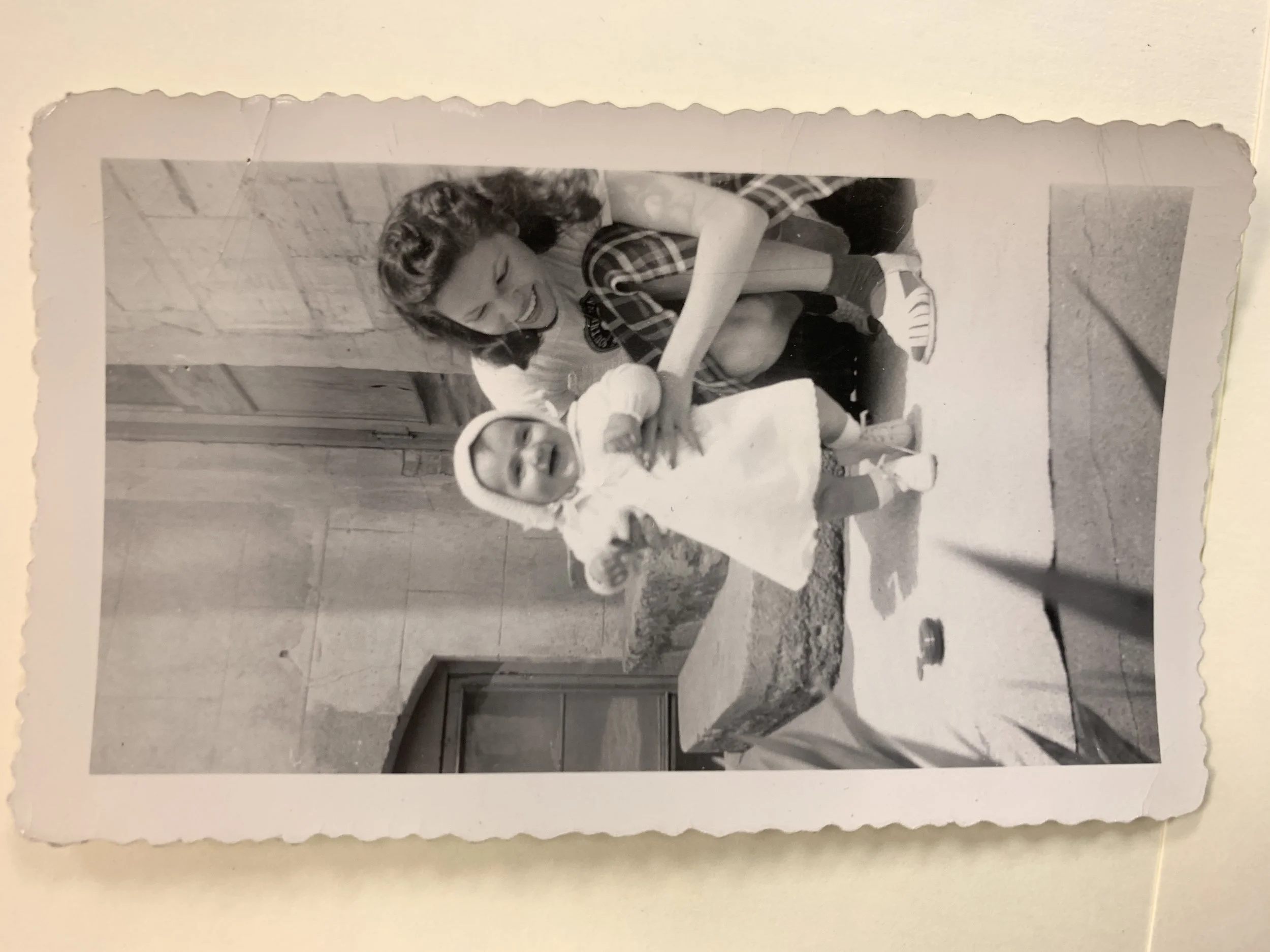

when they were seniors, the girls were moved to a separate "Senior House," where they learned domestic skills like how to cook and clean and keep house, and also were given a baby to learn how to raise one. You read that correctly: an orphaned Native baby girl was handed over to a house of high school seniors, so that they could learn how to change diapers and bathe and feed a baby. The girls took turns on baby duty, and scheduled their class time accordingly. My mouth hung open for the entirety of this anecdote. This didn't just happen when Virginia was a senior! It happened multiple times, over many different years! The baby that Virginia took care of was named Anne, and was eventually adopted by St. Mary's headmistress Bernice Holland.

Aimed with this new information and these new stories, we googled around until we found info on a Historical Society of Springfield, that housed a museum. We called them, to tell them that we were doing research on St. Mary's school and wanted to see if they had any photographs or documents in their archives, and asked what their hours were, as we tried to change our plans to drive to Springfield. The woman on the other end of the line very sweetly answered, "Oh, well... the museum was actually my father's, and he passed away recently, and I haven't known what to do with it, so it hasn't really been open recently... but if you tell me when you get here, I'll just walk over and open it up for you."

On our way to Springfield, we met with a woman named Davidica who lives on Pineridge, who is a historian and activist, and was able to give us more information and context about the history of Boarding Schools in the U.S. Starting in 1891, there was a “compulsory attendance” law that enabled federal officers to forcibly take Native American children from their home and reservation, and essentially required Native parents to send their children to boarding schools. Parents could be locked up for refusing to hand over their children, and even though over time some parents did find ways to avoid this, this law wasn't formally overturned until 1978. As you might imagine, and maybe already know, many (if not most) of these boarding schools were horrendous, and were sites of a lot of child abuse: physical, religious, and sexual, depending on the school. There is a tumultuous and dark history of Boarding Schools for Native American children. It was important for me to learn about this to give more context to St. Mary's, though based on the testimonies I've been able to collect, it seems like (at least in the 1940's) St. Mary's was perhaps one of the best (if not the best) possible options (given the deeply problematic system). Many families saved a lot of money to be able to send their daughters to St. Mary's, and it had a very good reputation of treating girls well, not using corporal punishment (unlike the comparable Catholic school), being more lenient towards girls who spoke Lakota, and generally being a place that prepared students for a continued education. Virginia spoke about her time there as though it was one of the best things that could have happened to her. She felt that her time at St. Mary's had allowed her to go on to get a college education, and become a published author, and she felt the school prepared her much better than other schools would have, at the time.

Lois Antoine also felt that St. Mary's was one of best things that could have happened to her. She was one of ten children, and the only one to go to St. Mary's, when her grandmother saved the money to send her. She considered it a huge gift and knew how lucky she was to have been the one to go. Today, Lois is 92 years old. Charlie and I met her in Rosebud, and she was kind enough to sit with us for a few hours to share what she remembered of her time at St. Mary's. Lois graduated from St. Mary's in 1945, the year before Nana was there. She didn't know Nana, but like Virginia, she spoke about the itchy wool tights, the awkward school dances, the baby she took care of as a senior (!), and learning to play the organ. She also recounted a story about "being bad" when she and a friend started walking across the frozen-over Missouri River one winter, and the ice started to "Pop" beneath them, so they had to run to make it back. They managed to, but ended up soaking wet.

Lois Antoine during her junior year at St. Marys. (top right)

Lois told us about the rationing during WWII, which affected what they were allowed to cook, and also prevented them from going home to visit, because of the gasoline rationing. Lois's eyes lit up when she spoke about being top in her class in science, and falling in love with the nursing uniforms of a nursing college that she dreamed of going to when she graduated. But a terrible bout of tuberculosis destroyed that dream, and instead, she stayed close to home. She ended up having five children, one of whom returned from war with terrible PTSD and a schizophrenia diagnosis, for whom she is the fulltime caretaker, even now at 92. She has 16 grandchildren, some of whom live with her in the house she owns. She is as sharp as a tack, and extremely tall, which just made me fall more in love with her than I already had.

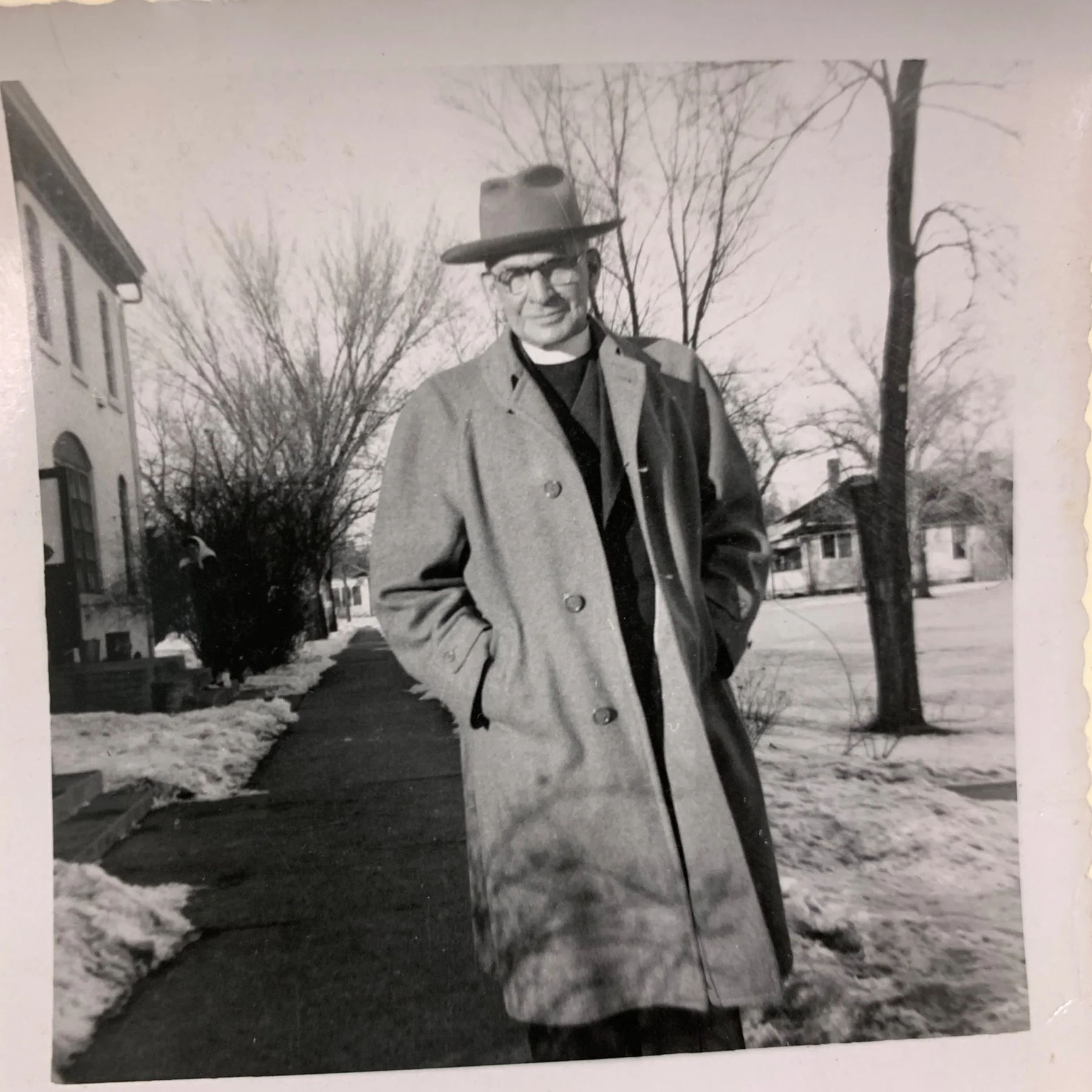

After Lois, we met the Reverend Webster Two Hawk, an elder who was at one time a Chief, as well as an Episcopal Reverend. He wasn't a student at St. Mary's, of course, but he was able to tell us more about what life would have been like on Rosebud during (and immediately after) WWII. Most notable to me, was his story about being required to take all the lightbulbs out of the lamps at night. Because South Dakota is so flat, they were told that bomber planes might be able to see them if they had their lights on, so everyone had to turn out all the lights and roll down the window shades at night. But many Lakota people took advantage of this predicament to hold their Yuwipi ceremonies in the dark, which were illegal at that time. With the lights out and the shades down, none of the non-Native authorities could tell what was going on inside. I was most fascinated by the way Webster was able to speak about both Christianity and Lakota traditions without any contradiction. They coexisted for him, and did not seem to interfere with each other at all. He mentioned that sometimes these days, he is asked to come to senior homes where Native Elders are living, and he sometimes says the Lord's Prayer in Lakota, which is soothing to many of them. I asked if he would say it for us, which he did, and while I listened, I thought about my Mom's story that, a long time ago, Nana had said the Lord's Prayer in Lakota to her as a kid. (Like the history of Boarding Schools, the history of Christianity in Native American families and the widespread converting efforts, religious abuse, and exploitation of Native communities is immensely wrought and problematic, but the fact of the matter is that today there are many Native folks who did convert, and have lived like Webster—with both Christian faith and Lakota traditions as part of their lives and their family's lives.)

Webster Two Hawk

Springfield Historical Society Museum

After meeting with these three elders, we made our way to Springfield, South Dakota and the Historical Society's Museum. The owner of the museum (who inherited it from her father), Marilyn Stone, was there to meet us, and let us into this unbelievable treasure trove of local history. It is hard for me to describe it in a way that would do it justice. Imagine rooms upon rooms of lovingly-made exhibits: a recreation of a prairie farmhouse from the 1800's, a display of the evolution of the modern typewriter, a wall of Springfield High School's graduating class photos over decades of time. A room of microfiches and physical newspapers, stacked and decomposing, dating back to the early 1800's. Bookshelves of photo scrapbooks donated by local families. Slides in boxes. Varsity sweaters. It was tremendous and utterly overwhelming. I could have spent weeks in there and only scratched the surface. But we didn't have weeks, so we rolled up our sleeves and started digging. The biggest finds of the day, were a photo of the St. Mary's building itself, and a photo taken at a school dance. The museum also had postcards from the 70's, of the St. Mary's building and the view from the school, and I took a few to send you. (I think Ma delivered a little set to each family.)

As the light dwindled on my last day in South Dakota, we hopped in the car, and Marilyn directed us towards the site of where St. Mary's had been. As we drove up, the sun was setting, and I got out of the car to look at the view that Nana would have seen when she taught there. There is a little lookout that someone has built, where you can stand and look across the Missouri river, towards Santee. It looks like a long distance to try and walk or swim, and I thought about Lois trying to run across it's frozen surface, with the ice popping beneath her. I thought about how many more questions I have now. I thought about being a twenty-three year old Japanese American woman arriving here alone, in the middle of winter in 1946, while your parents and brother are so terribly far away, stepping into the complicated world of Native American Boarding schools, and being given a building of young women to take care of, many of whom were also terribly far from home, and feeling alone in the world as well. And then I thought about what it might have felt like to spend five years having adventures, alone and independent, only to be summoned home to get married and leave it all behind. I wish I had asked her more questions when she was still around to ask them.

Sara standing on the edge of the Missouri river.